Organizing for ESG

ESG: Whose Job is it Anyway?

By Valentina Fomenko, CEO, Strategy DNA, Inc.1

Companies today face increasing pressure to demonstrate a commitment to sustainability. This is increasingly communicated in the language of ESG: Environment, Social, and Governance.

As non-financial compliance obligations, customer expectations, and investor demand continue to grow, and companies themselves are exposed to greater climate-related risk, the trend towards ESG shows no sign of abating. In a recent survey, 46% of respondents said their company has increased its focus on ESG this year, while 41% said current effort levels will continue.2

Furthermore, the IDC has estimated that ESG business services spending will grow to $158 billion by 2025, with a five-year compound annual growth rate of 32.3%.3

Under several names, sustainability has been part of the corporate structure for some time. First coined as the Triple Bottom Line4, sustainability was understood as a broadening of the traditional financial bottom line to include a company’s social and environmental impact.

In a departure from its original impetus for a wholesale rethinking of capitalism, the business case for sustainability was understood as a preventative measure to reduce or eliminate costs related to mitigatory action for social or environmental issues. This could include fines, fees, or excess maintenance costs resulting from issues such as climate change or community opposition. This approach, in its common incarnation, lacks focus, which can lead companies to greenwash, or end up treating sustainability as a nuisance rather than an opportunity.

It was followed by corporate social responsibility, or CSR, which moved the focus on license to operate and stakeholder accountability. A direct challenge to the incumbent paradigm of shareholder capitalism, CSR required companies to demonstrate good corporate citizenship.

This typically took the form of discrete philanthropic initiatives and stakeholder engagement events. As with the Triple Bottom Line, CSR initiatives tended to lack meaningful KPIs and a systemic implementation.

Nowadays, corporate sustainability is synonymous with ESG: environment, social, and governance. The ESG trifecta collectively represent what a sustainable company is supposed to look like. ESG, which is currently a muddled space, is on a clear trajectory towards harmonization, as the many different frameworks begin to show signs of unification. As of writing, the Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the United States is preparing to require corporations to include climate liabilities, risks and opportunities in their disclosures to investors. In May of 2022, it also proposed amendments to rules and reporting forms to promote consistent, comparable, and reliable information for investors concerning funds’ and advisers’ incorporation of ESG factors. So how could the product, strategy, and operations of the business from an ESG perspective be used to create more value for customers, shareholders, and stakeholders?

The Sustainability Officer, Transformed

As corporations scramble to meet the mold of a sustainable company, they look down upon existing sustainability professionals. However, the potential of the role was rarely appreciated, sustainability professionals were left to carve out what authority they could.

Sustainability professionals have not been empowered to drive a systemic view of sustainability, which would require their role to touch on many different core functions of the business. As ESG took off, the positioning of the sustainability professionals in the organization has remained largely the same, and their role has often remained primarily as an environmental function, which was something sustainability officers were able to wrap their arms around and the turn they were able to claim.

The integrated perspective of ESG—that considers the systemic relationship between non-financial performance on environment, social, and governance—is causing friction with the established role of the sustainability professional. The sustainability or ESG function of the business finds itself unprepared to hold responsibility for this holistic definition of sustainability, many aspects of which sit outside the jurisdiction of their job responsibilities. It is no wonder many find themselves flatfooted when other more established business functions like HR embrace key issues like diversity and inclusion or the social aspect of sustainability. To some degree, this is a terminology issue. But it is also the result of poorly defined “social” and “financial” pillars and never truly operationalized. The potential for duplication with existing, more powerful corporate functions, such as Finance or HR, only compounded the issue.

We have about 30 years of sustainability thinking that sees sustainability as primarily and functionally in environmental terms. Continuing to do so, when the thinking has evolved far beyond, leaves the space at a marked disadvantage.

To be effective, sustainability needs to be defined much more broadly and integrated with the company’s ability to profit and grow. Effective integration must connect sustainability to these commercial growth levers, such that sustainability has direct influence over areas such as brand value and customer experience. To achieve genuine sustainability, corporations need to solve this integration problem.

Yet, ESG as a corporate function is struggling to integrate itself among other critical business functions. As a result, significant confusion exists among business leaders over where ESG should sit within the organizational structure.

Now that companies are expanding sustainability into new programs with an ESG-focus, where to locate the sustainability function to achieve optimal results has become a crucial question. Who should sustainability professionals report to? How high in the organizational chart does the function need to sit in order for meaningful decisions to be made?

To answer this question, we have looked into the current best practice for the functional alignment and optimal operating model for how companies can make the most of their sustainability function. We have collected the company size, industry and ESG rating of each company in the Fortune 1000. The ESG rating has been taken from the CSRHUB,5 which is a reliable source on consensus ESG ratings, and feeds into global investor tools such as Bloomberg, D&B, LexisNexis, and others. This was treated as a measure of actual performance, for the purposes of this analysis.

Surveying the presence of ESG or sustainability related positions in the highest tiers of Fortune 1000 companies, we sourced positions from publicly available organizational charts available through The Official Board, which makes organizational charts available to the general public.6 The function of these positions were then coded as either “Focus” or “Alignment” based on the main job responsibilities,7 and its upward reporting relationship respectively.8 As the Official Board does not cover lower levels of organizational hierarchies, our analysis is limited to the upper tiers of organizations.

The Proof Is in the Pudding

We have hypothesized that the level at which a sustainability or ESG professional is placed within an organization directly impacts the ESG performance of the company. We suspected this would be true across industries and company sizes. Organizational charts for all the Fortune 1000 companies were reviewed to identify whether ESG/sustainability positions were present.

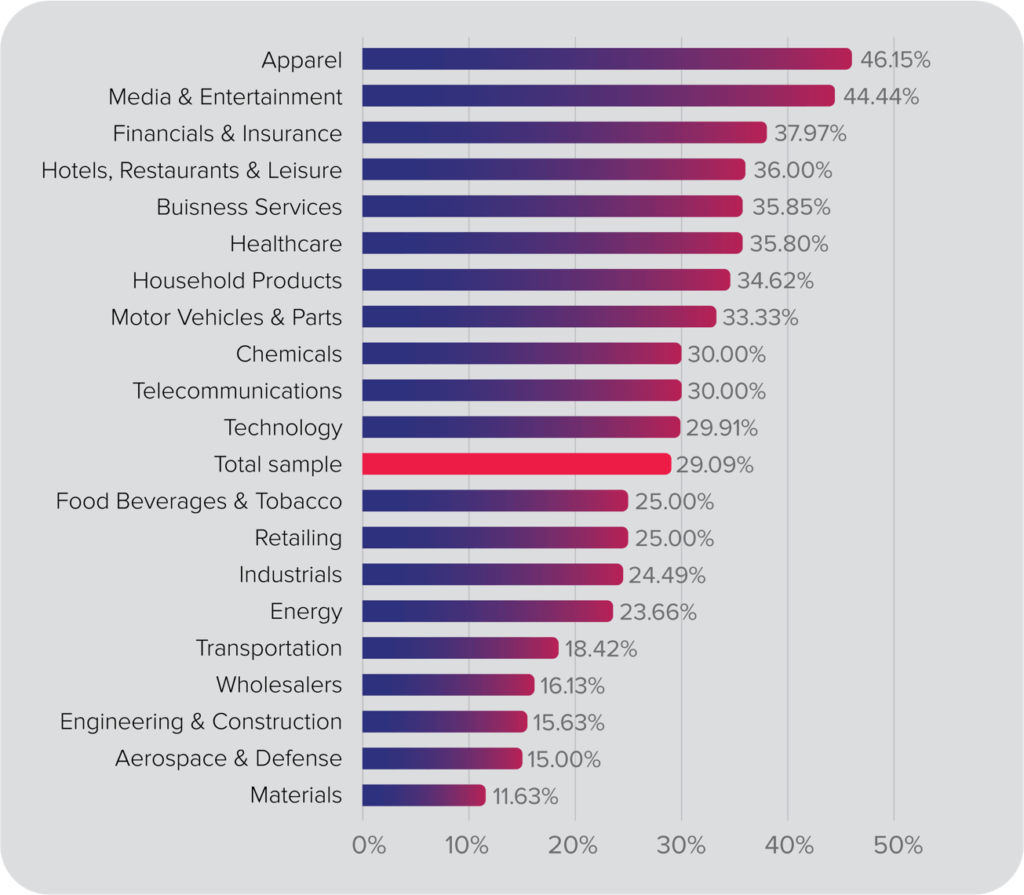

Out of the Fortune 1000, we found that only 219 companies had sustainability or ESG related positions at the upper tiers of the organization, as shown in Figure 1. The rest either had these functions below the top tiers of the organization or these functions were not reflected in the organizational chart at all. To better understand the relationship between a company’s ESG score and these factors—whether the company has sustainability professionals in the upper tiers of the organization, the industry, and the firm size—we analyzed results using an ANOVA. The results of which are indicative that the level of the position in the organizational hierarchy, the company industry, and firm size all have a significant impact on the ESG score of the company.9

Figure 1. Proportion of firms with upper tier sustainability positions across industries

Source: The Official Board, Strategy DNA analysis

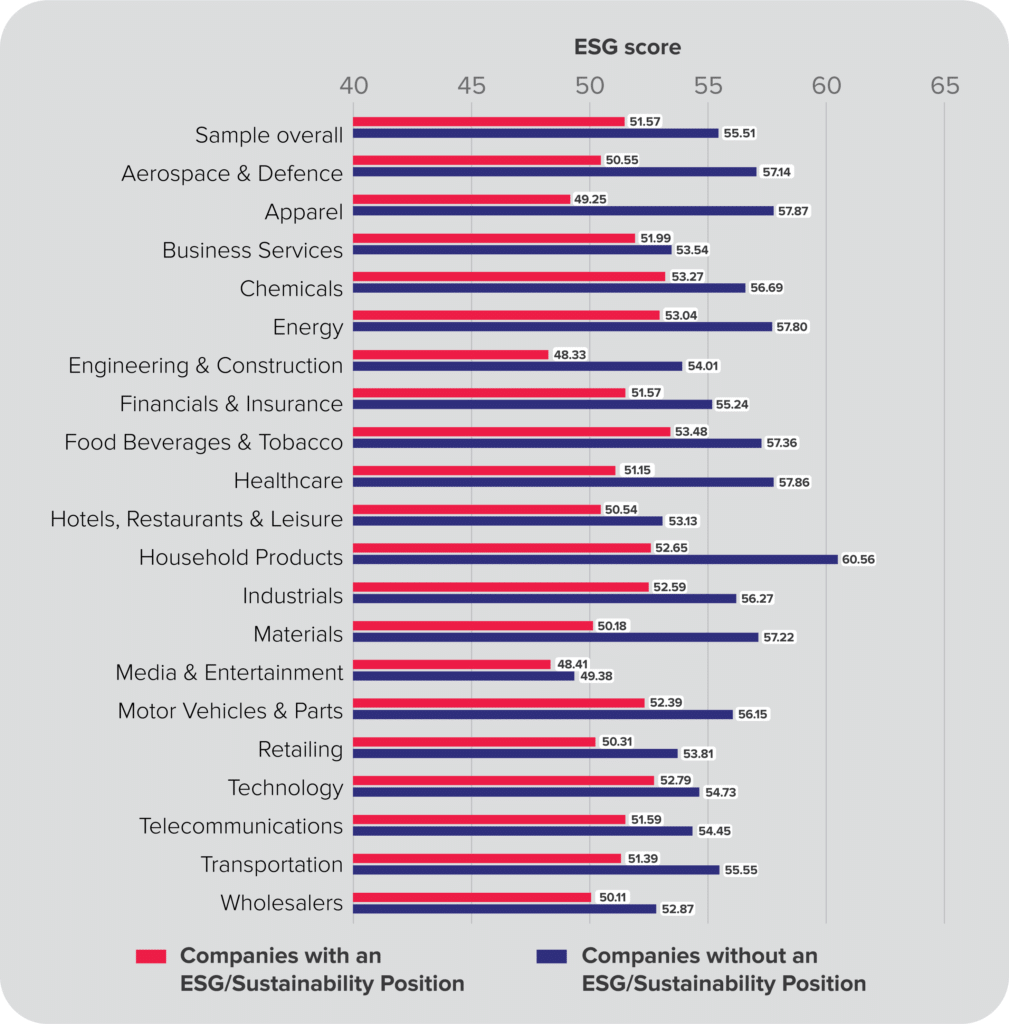

To validate our hypothesis against the control group, a t-test was performed to determine the statistical significance of these findings.10 The comparison of ESG scores between companies with and without sustainability/ESG professionals found that in the same of the Fortune 1000 companies, firms with sustainability/ESG positions in place show higher ESG rating scores than firms without an ESG/sustainability function.

Across industries, companies with a sustainability function had significantly higher ESG ratings. This trend was most visible in apparel, household products, and materials industries. It was also significant in aerospace & defense, engineering & construction, and healthcare. The presence of a sustainability professional had the least impact on ESG ratings in the media & entertainment industry, closely followed by business services.

Figure 2. Differences in ESG performance between firms with ESG positions and firms without ESG positions

Source: The Official Board, Strategy DNA analysis

The level at which a sustainability professional exists within the organizational structure can be understood to be an indication of how important sustainability is to that organization. It can also represent the siloing of sustainability within an organization—a sign of poor integration.

Focus: Risk vs. Value

Given the potentially infinite scope of the ESG function, it is important to pay attention to how companies define it for themselves. For many companies, the current focus of sustainability is heavily influenced by a legacy function it has expanded into. For others, the size and operating models do not support a standalone sustainability or ESG position, so it becomes rolled into something else. The underlying focus of sustainability/ESG positions in different industries distinguishes whether the approach being taken is one of risk avoidance or value creation.

When risk is the dominant approach, we often see sustainability containing an outsized focus on training and development that lacks in a broader strategic context. While important issues like diversity and inclusion and climate are viewed with urgency, they are likely to be treated separately from sustainability. A risk-dominant approach tends to be focused on crisis intervention and reputation management, and reports to an organization’s HR function. Other regulatory or compliance-heavy reporting functions, such as investor relations, can also signal sustainability is being defined from a risk management perspective.

Value orientation on the other hand, is more difficult to pinpoint. That being said, a focus on strategy development and commercial issues are common indicators. To understand the focus of ESG/sustainability positions in all Fortune 1000 organizations surveyed, we have analyzed the positioning of a role in an organization, along with its reporting relationship.

Across industries, approximately 30% were found to have a strictly sustainability/ESG-focused role. There were more ESG positions in industries with a stronger reliance on customer-facing activities (such as apparel, media and entertainment, insurance, hospitality), although there are exceptions here, such as companies in retailing industries, which have a relatively low prevalence of sustainability/ESG professionals.

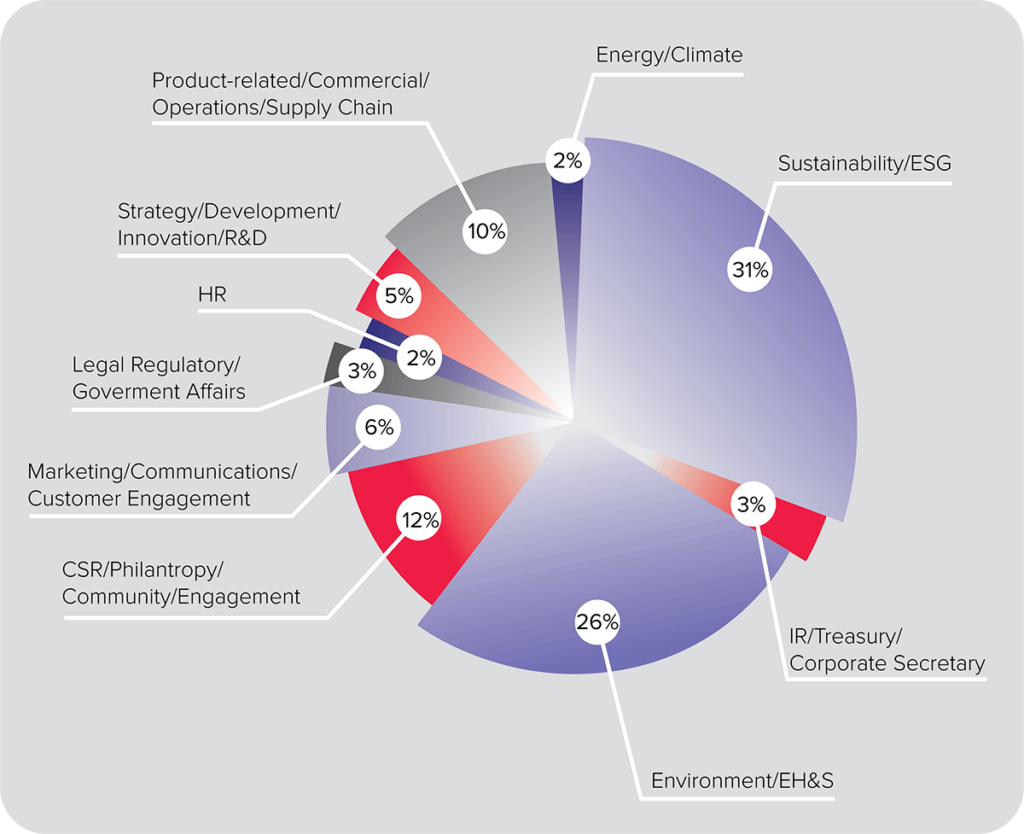

Figure 3. Predominant focus of sustainability and ESG-related positions

Source: The Official Board, Strategy DNA analysis

The focus of sustainability/ESG positions varies by industry. This was mostly split between investor relations, finance, supply chain, or within environmental health and safety, and occasionally strategy. In cases where sustainability was wrapped up with another organizational function (hybrid model), this signals there is a functional alignment with company strategy and ESG objectives. These were a small minority of the Fortune 1000, with only 5% of sustainability positions having a clear focus on strategy. In comparison, 26% focused on Environment, Health, and Safety.

While the efficaciousness and maturity of an organization’s sustainability can be a result of focus—or functional alignment—it is not necessarily a causal factor. Focus is to a large extent driven by the industry, and there are significant differences in how this is distributed depending on the issues and constraints of a sector.

Even if the present focus of sustainability is generally accepted by industry leaders, it is important to recognize possible limitations. For example, having an outsized focus on legacy environmental issues, common in companies within heavily regulated industries such as chemicals or energy, is intrinsically limited because it prompts companies to assign responsibility for social and governance matters elsewhere.

On the other hand, for companies in industries where customer relationships have a more direct impact on revenue (retailing, media and entertainment), public relations is a central

concern which often results in a strong focus on discrete philanthropy and stakeholder engagement.

While a lot of these differences make sense and have good reasons behind them, the next level challenge as companies’ ESG approaches mature, is to transcend organizational silos and take ESG to the level of strategy.

Integrating sustainability with strategy requires engaging leaders across the organization to give voice to the entirety of the environment, social, and governance topics. This is likely to change or expand the scope of consultation across the business, placing greater importance on positions like the Energy Manager, for example. Diverse lines of communication across the business can be strengthened by connecting executive compensation to ESG goals. The financial incentive for executive management has been shown to drive accountability and the progress of the sustainability agenda.

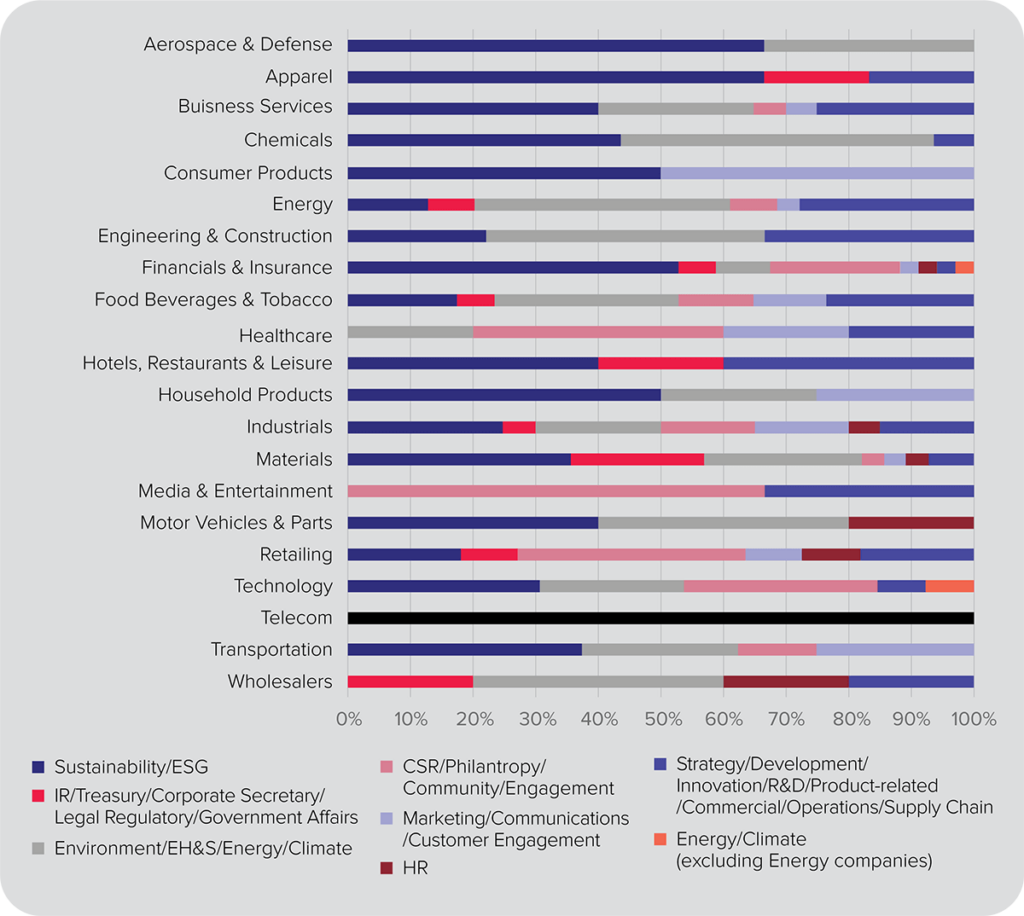

Figure 4. Focus on sustainability/ESG-related positions across industries

Source: The Official Board, Strategy DNA analysis

Who Should be the Boss of ESG?

How a sustainability/ESG role is positioned within an organizational hierarchy is a good gauge of what is important to the company. For example, if a role sits within the organization’s communications department, this indicates that sustainability is being considered from a CSR and public relations perspective. In contrast, if sustainability is part of the HR department, it is more likely to be taking a holistic approach that revolves around generating value as opposed to avoiding risk. Where sustainability sits in strategy, it shows that an organization is trying to integrate sustainability across all aspects of the business and company objectives.

Vice President and Chief Sustainability Officer at Genesys, Bridgette McAdoo, advocates for the latter, which she has found to be the key to a successful program, “at Genesys, we want [sustainability] to be a foundational truth to who we are; our organic extension of how we are empathetic to not only our employees, but to our customers and our key stakeholders.”

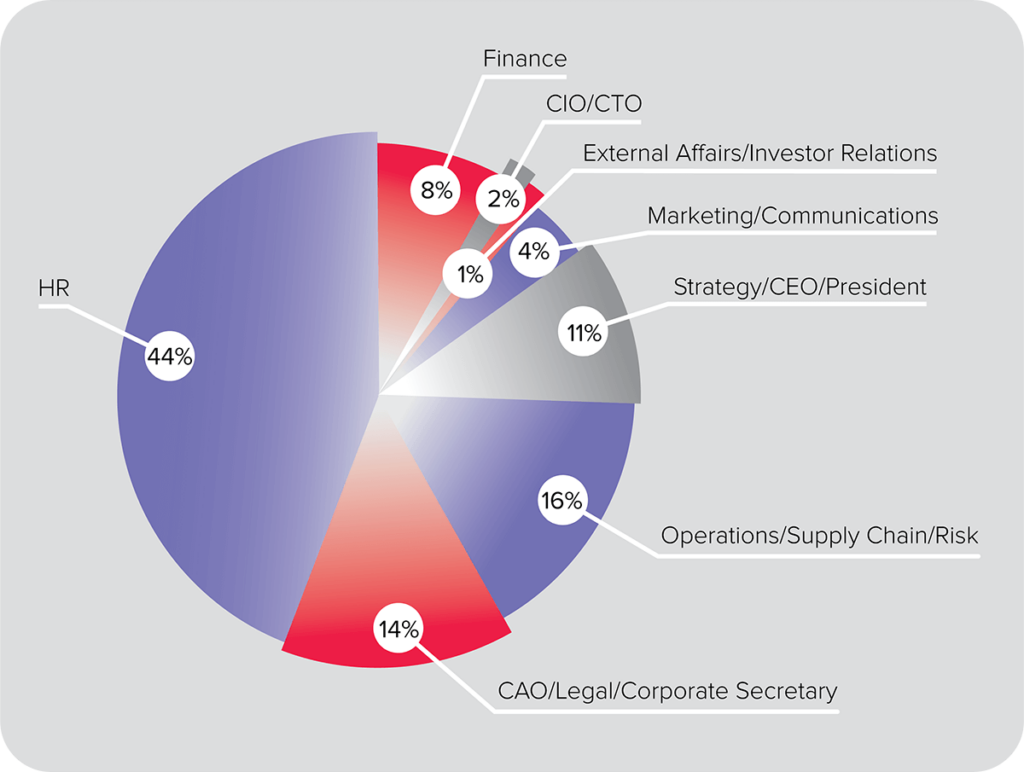

Figure 5. Functional alignment (reporting relationship)

Source: The Official Board, Strategy DNA analysis

In our analysis, the alignment was determined based on the position title and the upward reporting function. Similar to focus, alignment is also somewhat dependent on industry: a legal and regulatory officer is important for utilities and heavy industries, while not so much for an apparel retailer. For apparel companies, marketing communications are a very important part of their product-focused business, which can explain the higher prevalence of sustainability professionals in that industry (44%), when compared to raw materials (12%), construction, transportation, and utilities.

Looking at the functional alignment—or reporting relationship—for ESG/sustainability positions surveyed, the HR department presides over a disproportionate share. This is followed by positions which report to operations/supply chain/risk and CAO/legal/corporate secretary.

In comparison, a very low number of sustainability positions are aligned with finance and strategy/CEO/president categories. This is problematic because these reporting relationships allow for more access and impact ability.

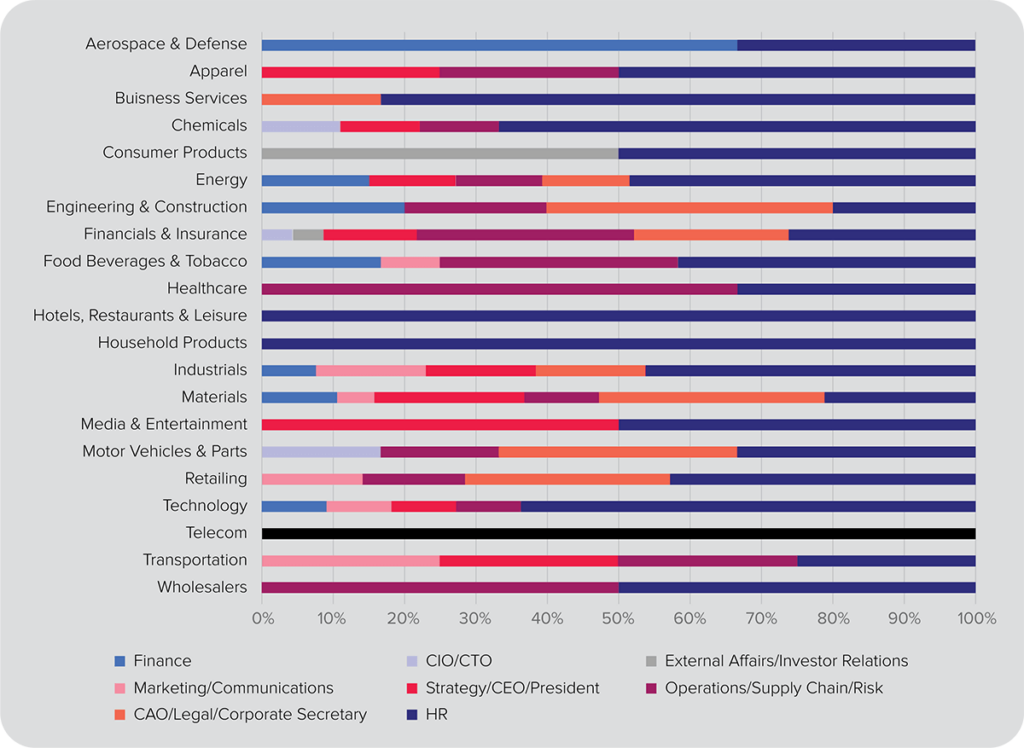

Figure 6. Functional alignment (reporting relationship), across industries

Source: The Official Board, Strategy DNA analysis

In terms of industry, sustainability professionals reported to strategy/CEO/president for half of media/entertainment companies surveyed, and about a quarter of apparel and transportation companies. Only one-tenth of chemicals, energy, finance/insurance, industrials, materials, and technology companies were aligned to strategy/CEO/president, while wholesalers, retailing, motor vehicles/parts, household products, engineering/construction, consumer products, healthcare, hotels/restaurants/leisure, food/beverages/tobacco, and business services showing no alignment to strategy whatsoever. The industries with sustainability positions most tied to the HR departments were household products, and hotels/restaurants/leisure.

What’s Next

There may come a time when we no longer need sustainability to be championed within the organization by specific professionals. This would not come as a result of waning importance, but rather, the full incorporation of sustainability in the business-as-usual scenario. As adoption gives way to action, and companies embrace results, we now find ourselves in this transition phase. Effective navigation of this period will require sustainability professionals to appreciate the ultimate purpose of their position. If full integration is where sustainability is headed, professionals in the field need to become strategists.

Our analysis has shown that sustainability professionals with a focus on strategy and positioning near top decision-makers within an organization are ideally situated to measurably improve the sustainability of that organization as a whole. To support the transition from an CSR approach, characterized by social and environmental risk orientation, to an ESG approach, marked by value creation, company strategy needs to be aligned with sustainability.

The importance of embracing strategy for sustainability professionals is endorsed by veteran chief sustainability officer Bridgette McAdoo, who notes that, “a whole lot of organizations are trying to compartmentalize sustainability. But what sustainability is truly supposed to be, is a cross-functional holistic approach that addresses everything as one strategic imperative.” Sustainability/ESG needs to be strategy-led; an organizational function emphasizing the substantive rather than the performative.

Our biggest challenge along the way is knowing what good looks like. At present, sustainability in many companies is siloed, and there is poor communication between initiatives, reporting, and high-level organizational strategy. Current practice provides examples of different, yet effective, ways to approach the organization of sustainability within a company but have yet to produce best practice consensus. But it has also shown the limitations of legacy approaches, which often limit—either through a narrow focus or ineffective reporting relationship—the scope and power of the sustainability professional to impart meaningful impact organization-wide.

Seizing strategy is something George Bandy, global sustainability leader in ESG and circularity and former head of circularity at Amazon, sees as crucial to the success of the profession and global climate action goals. Bandy believes that “sustainability officers should be placed right underneath the CEO, who is responsible for the vision, purpose and energy of the organization; the person who is responsible for sustainability needs to be on the senior leadership team so they can communicate with the senior leadership team about the best way to collectively succeed”. With sustainability roles positioned in the right place, assessing organizational vulnerabilities can be properly encouraged, and a company can honestly pursue its own restoration efforts, but also be proactive with respect to future challenges.

Corporate leaders searching for a functional home for ESG would benefit from considering the approach being taken to align materiality and strategic company pillars with the functional structure of the company. To bring together all components of sustainability/ESG identified through a materiality assessment, it is best to align the narrative being presented by the sustainability function, with the value and mission articulated by the company. By fostering strategic alignment around how ESG performance can support and strengthen a company’s strategic goals.

1 Special thanks go to the following contributors to the project: Rebecca Sokolov, Sajil Mehta, and Oleksii Sukhoi.

4 25 Years Ago, I Coined the Phrase “Triple Bottom Line.” Here’s Why It’s Time to Rethink It.

5 Respected due to a relatively high degree of transparency around its data schema and rating rule.

7 Deciphered from the title of the position.

8 Based on information present on the publicly available organizational chart.

9 Company size estimated by revenue. The log function was then used to reduce variability of results. To further test this hypothesis, regression was used to isolate the impact of certain factors, and determine whether impact, if found, was statistically significant. Controls were established for factors such as industry and firm size. As a robustness check, a chi-squared test controlled for industry type and company size to test the direction and magnitude of each on ESG performance. The findings indicate that having an ESG-focused position in the higher tiers of an organization is more likely to lead to companies having a higher ESG performance score.

10 To avoid possible issues with data distributions, bootstrapping (1000 samples) was performed as recommended by Field (2013)